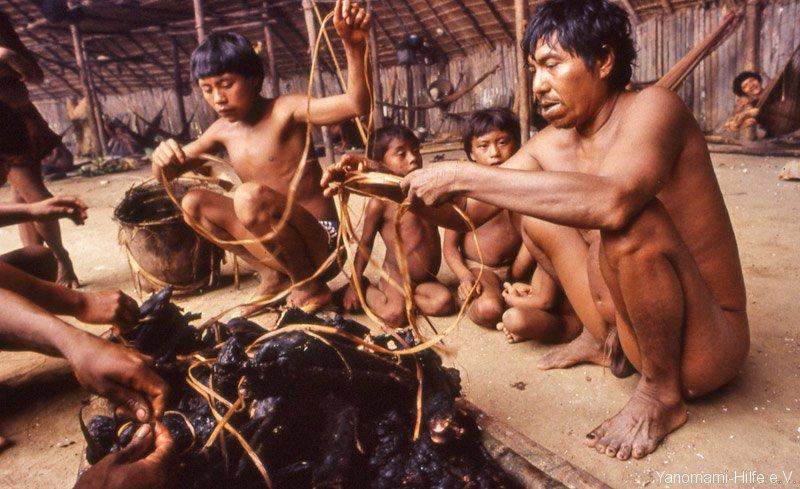

Endocannibals of Yanomami tribe

The widespread interest in cannibalistic Indian tribes arose in the popular culture in 1980, after the release of the "Cannibal Holocaust" film by an Italian director Ruggero Deodato. The movie was a fake documentary said to be assembled from a gory footage of a film crew, who were trapped, mutilated and eaten by the Yanomami tribe living in the forests on the border of Brazil and Venezuela.

The widespread interest in cannibalistic Indian tribes arose in the popular culture in 1980, after the release of the "Cannibal Holocaust" film by an Italian director Ruggero Deodato. The movie was a fake documentary said to be assembled from a gory footage of a film crew, who were trapped, mutilated and eaten by the Yanomami tribe living in the forests on the border of Brazil and Venezuela.

In reality, modern Yanomami do not trap and eat travelers - they are endocannibalistic. Endocannibalism is a practice of eating the flesh of a person, usually a dead relative, after they died. Yanomami believe that this helps them preserve the tribe's unity.

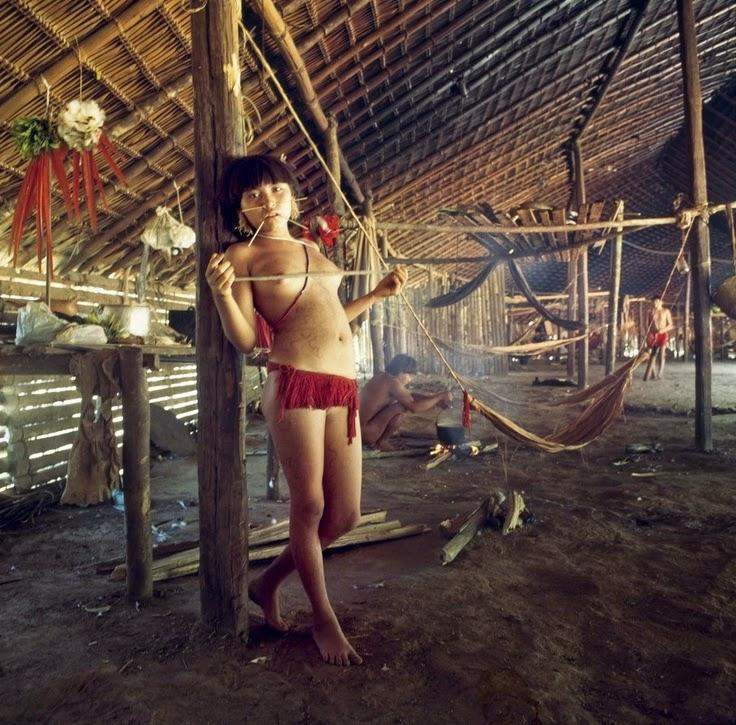

Yanomami live in impenetrable tropical forests, and their population is estimated to be about 35,000. Their houses are called Shabono or Maloca – circular huts constructed of thatched palm leaves and wood, built in clearings in the jungle. Usually, multiple shabonos surround a central open space. Small huts can have 40-50 people living inside, and bigger ones accommodate up to 250 people. Families do not have separate huts.

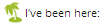

The everyday life of Yanomami does not revolve solely around eating human flesh. Their whole life is quite hard and monotonous in their constant struggle for existence: they collect fruits, vegetables and roots, they hunt and fish. Their primary food is bananas and cassava. Yanomami use different poisons for hunting, such as curare, and believe that gods make them resistant to the poison. A Yanomami man can eat a half-cooked piece of meat of an animal killed by a poisoned arrow, while travelers who visited their tribe and tried to do the same, died. They also eat fish, catching it by throwing poisonous plants into a fenced off section of the lake and then gathering it.

As to Yanomami's endocannibalism – not all of the customs remained till today. When a member of the tribe dies, the whole village gathers to commemorate the event. They burn the body of the deceased on a funeral pyre, because the soul can only achieve a full salvation if the body is burnt. During the cremation, the villagers cry and sing sad songs, with their faces painted black. The burnt remains are then crumbled and put into a big pot, where they are kept until the second part of the funeral ceremony. It could take a long time before the second part of the ceremony is conducted – Yanomami usually delay it until an upcoming festivity. The second part consists of cooking bananas, mashing them and mixing them with the ash and bone of the dead. All the village gathers up to eat the mush – this way, the soul of the tribe member is absorbed by the tribe again and freed for salvation. If they don't perform this ceremony, they believe that the soul of the deceased will be forever trapped between the world of the living and the world of the dead.

Yanomami always sprinkle their food with ashes – they simply don't have any salt. If it happens that a visitor brings them some salt, they eat it greedily and close their eyes with pleasure, as if it was sugar or honey. They also love smoking and chewing tobacco, cultivated on their tiny fields, and use the bark of the Virola theidora tree (also known as epena) to make potent psychoactive snuff, adding ashes from the bark of Elizabetha princeps, which they call ama, ama-asita, or chopp. The snuff is used in various rituals.

Death is a very important matter to Yanomami – they are convinced that the soul has to be protected after death. They care about the dead in a special way – the most terrible situation for a Yanomami is if a member of the tribe gets killed in the forest and the others can't find his corpse. If two Yanomami members are enemies, they threaten each other by not eating their adversary.

Being omnivores, Yanomami never hunt eagles, monkeys, or otters, because they believe that the first two are reincarnated tribesmen, and the latter are reincarnated tribeswomen. If someone kills an otter, this means that a woman or a child in the tribe will soon die. Because of this, they hunt very carefully.

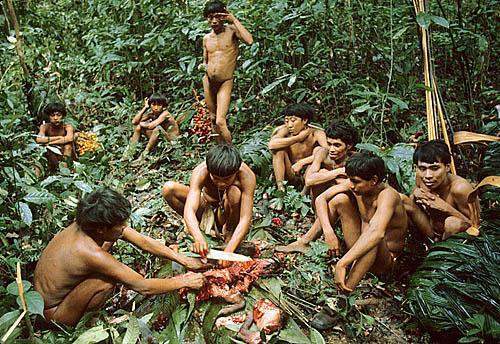

Only grown men can become hunters. A Yanomami male is considered an adult when he masters “vayamo” - a special language to communicate between the members of different tribes. For a woman to be considered adult, she goes through rites of passage – after her first period she is locked in a small cage for a month and don't feed her for the entire first week. When the imprisonment is over, her older female relatives free her, paint her body and present her to the villagers as a new woman. Yanomami believe that if this ritual is not performed, their village will be washed away by a flood.

Marriage and divorce are not accompanied by any special rituals. The groom just comes to the hut where the bride-to-be lives, works for her family and then settles with the bride. To divorce, a woman can just find another man, hang her sleeping mat next to him and that's it. Of course, the ex would fight with the new husband by hitting each other with sticks, but fighting to death is forbidden. Yanomami also kidnap women from the neighboring villages to avoid having inbred children. Birthing a child involves a woman going outside of the village with her older female relative. If the woman already has children, she kills the newborn. If the newborn is weak or born with disabilities, the child gets killed as well. If it's twins, the strongest looking one gets to live. However, if a woman breastfed the newborn, she can no longer kill it.

Naturally, the tribe has its healers. However, these healers couldn't cure deceases brought by the white people. In 1968, a group of ethnographers from the University of California at Santa Barbara visited the tribe. They brought 2,000 doses of vaccine against measles and vaccinated the tribesmen. Over a three-month period after the vaccination, the worst epidemic in the history of the tribe broke out. Between 15 to 20% of the tribesmen died in the epidemic. From 1987 to 1990, the Yanomami population reduced even further because of malaria, mercury poisoning, malnutrition and violence due to the influx of more gold diggers. In 1993, there was a Yanomami massacre outside of Haximu, Brazil – a group of garimpeiros (gold miners) killed 16 Yanomami. Deaths of their tribe members affected Yanomami in a horrible way due to their belief that the souls of their relatives are now lost forever.

Lately, many global awareness-raising campains were created to protect the tribe.

Leave a comment

0 Comments